By Dan Wilcock

There’s a reason why investing sages like Jack Bogle, Burton Malkiel, and David Swensen praise Winning the Loser’s Game by Charles Ellis. Now that I’ve read the book (just closed the cover) I know why. This book is a bullshit eliminator, completely clear-eyed about market risk (the fact that losses will happen) that nonetheless explains the stakes in not taking on market risk in a world where taxes and inflation constantly erode wealth. It’s a book that explains the counter-intuitive nature of the market in a way that clicks: why investors should welcome stock price declines, why booming stock markets are better for stock sellers than stock buyers, why stocks aren’t important because of their price but rather because of their ability to produce dividends. Even though these are well established interpretations of the market, their wisdom never sunk in before I’d read Winning the Loser’s Game. Hence I’d recommend it wholeheartedly as one of the best books on investing.

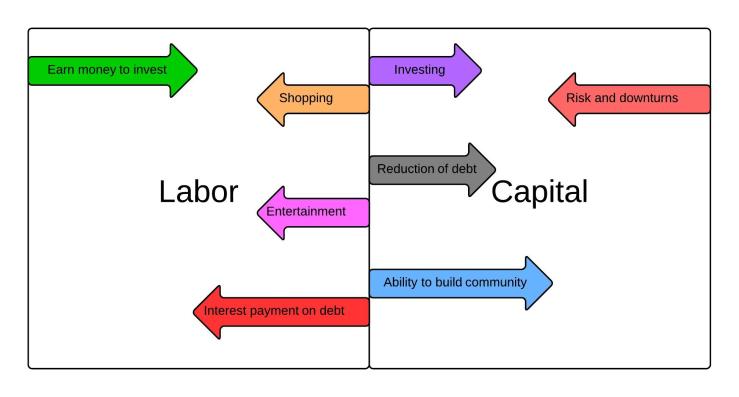

The title of the book comes from a journal article Ellis wrote in 1975. He compares investing to tennis, which for virtually every amateur is a loser’s game. The victor wins on their opponent’s unforced errors. Ellis argues that investing used to be a winner’s game, but the field got so crowded with experts and operators who know how to take advantage of all the suckers (my words, not his) that the only way to win is avoiding unforced errors. The biggest of these is attempting to “beat the market.” This is an endeavor where more than three quarters of professionals ultimately fail. The individual investor socking away money in IRAs and 401ks shouldn’t even try. Rather than losing by actively trading, and compounding those losses with all the fees this entails, investors should craft a realistic policy that seeks to capture the entire market return (through entire market indexes) or a segment of the market through selected low cost mutual funds.

I was already bought into the idea of indexing (the lowest cost, getting the most of whatever the market returns), but before reading this book I might have been more likely to shift my index holding to more bonds in a bear market to preserve value. This is psychologically understandable, but exactly the wrong approach. Big downswings require that investors stick to their policy and make the most of bear markets by sticking to the path they set. This is a more nuanced, and more practical, version of the old saying “buy low and sell high.” That simple saying doesn’t prepare investors to do the right thing. The phrase is premised on active investing, and when the markets are at their most volatile is when we as human beings are most likely to make precisely the wrong decisions. By staying the course, and investing in consistent intervals, buying low and selling high happen naturally. The market cannot be timed, according to Ellis. Jumping in and out of the market is, for most people, lost opportunity.

I read the 4th edition of this book. As of this 2014, Loser’s Game is now in its 6th edition and updated post-great-recession. If you’d like to know how Ellis deals with the market fallout from 2008, I’d recommend that version (which I haven’t read). I think, however, that the reader of the 4th edition would have been very well served throughout the last seven years. They would have stuck the course and rode the massive upswing in equities to their now record highs. They would also have established an emergency fund that would allow them to buy largely into equities and then be steely about holding them.

Anyway, after making it halfway through the book, which I’d borrowed from the library, I ordered a copy for my personal collection (4th edition, much cheaper than the 6th). This is a book that any investor would be well served to read annually, perhaps just before looking at results and allocation. The rest—virtually everything we read online in the financial news—is counterproductive noise.